The German development magazine welt-sichten (10/19) published a commentary by Ralf Südhoff on progress of the Grand Bargain agreements with the title:

Local aid workers are held back – humanitarian aid reforms are rendered futile if they are blocked by politics

Why is it more important than ever to know if humanitarian action can undergo fundamental changes? Firstly, because never before have so many people – over 130 million – been in need of humanitarian assistance. Secondly, because an ever-growing number of regimes and parties to conflicts are undermining the work, values, and goals of humanitarian action. The list of these regimes extends far beyond those in Damascus and Riyadh. It includes the regime in Washington, where Donald Trump has detained children on the Mexican border, deliberately refusing to give them soap, towels, or sheets to sleep on, as a way of discouraging further attempts to cross the border. It includes the regimes in Rome, Paris, and Brussels that are no longer rescuing those drowning in the Mediterranean. As a result, the UN estimates that one out of every nine migrants dies trying to flee across the Mediterranean to Europe.

There remains a need for a German foreign minister that is ready and willing to invest more political capital in humanitarian action.

When there is a lack of consensus behind the idea that people must help one another in times of emergency, it is clear that it is more important than ever for humanitarians to espouse their principles of humanity and neutrality and to underpin these with convincing and reform-minded work, instead of work serving organizational interests.

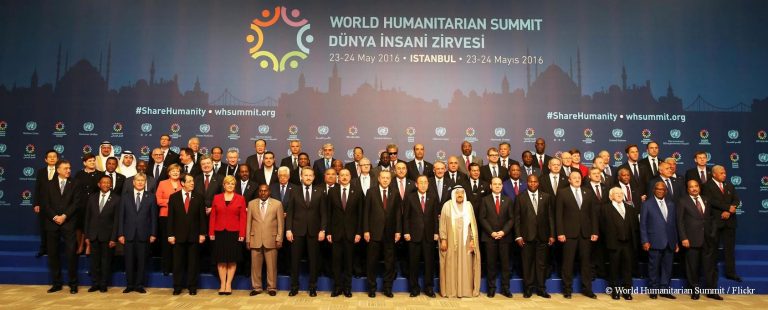

The good news from the recent report of the British Overseas Development Institute about the “Grand Bargain”, agreed to at the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul, is that people affected by crises are, to a degree, receiving assistance significantly more flexibly, less bureaucratically, and with more dignity than ever before.

Example – Cash Transfers: Today, cash is often considered the best form of emergency assistance in contexts with working markets. With cash transfer programmes, people in need can decide for themselves what they need most, instead of having that decided for them by Western organisations. Almost all signatories to the “Grand Bargain” have campaigned for further reforms in favour of cash transfers and many are expanding their programmes.

Example – Dismantling Bureaucracy: Complex and donor-specific reporting mechanisms have increased the administrative burden on organisations and have nearly driven aid workers insane. Thanks to, amongst others, the German government, the international standardisation of requirements and reporting mechanisms is already being tested by reducing this burden for pilot projects.

Example – Localisation: In Istanbul, both donors and humanitarian organisations committed to carry out over one-fourth of their assistance activities through local actors and partners by 2020. In the past years, donors like Germany have already brought this proportion up to one-fifth. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) created a mechanism allowing money for 13 crisis countries to flow though country based pooled funds (CBPFs) to be allocated directly in the context. The German federal government is one of the largest donors to these CBPFs, currently giving almost 220 million Euros per year.

Yet, this example of localisation also highlights to many the lost ideas and goals behind the promises of reform. In a recent study by the OECD, over 8600 people affected by crisis complained that assistance was still driven by the mandate of the implementing humanitarian organisation and was not completely need-based. This causes smaller organisations to, for example, give assistance where they already have access and not where is it most needed.

“Who needs what the most” is something often best determined by the people on the ground and that know the context best. The “Grand Bargain” should prevent these people from being marginalized by massive, multi-billion-dollar, international aid organisations. If one only looks at the numbers, this appears to be working quite well. However, localised funds include money that international humanitarian organisations give directly to local partners. Furthermore, funds from the CBPFs tend to flow to the local offices of international aid organisations. Truly local organisations have no say in how funding is distributed and have almost no direct access to funds themselves. These factors all contribute to the fact that only 0.4% of all humanitarian funding goes directly to these organisations. Finding this number absurd does not mean that one has to romanticise humanitarian assistance from below nor demonise locally-anchored international humanitarian action. Suffice it to know that an estimated 90% of assistance is provided locally, informally and, at least to an extent, unrecognised by the actions of neighbours, relatives, and entrepreneurs.

Still, the German Federal Foreign Ministry launched a new project in August, which will, in cooperation with Welthungerhilfe, Malteser International, Caritas International and Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe, support five local partners of each of the organisations in eight countries. Beyond this, German humanitarian organisations began receiving an administrative lump-sum with each project grant, which allows them to invest and support their local partners more flexibly.

Yet, each of these small steps toward the success of the “Grand Bargain” are useless if they are being undermined, and not supported, by political actors. New pilot projects and funding lines for localisation are useless if donors, as part of their nearly limitless counter-terrorism efforts, are making it more difficult for organisations working in the worst humanitarian crises to fund their local partners. Dismantling bureaucracy remains ineffective in conflict regions, if humanitarian organisations continue to face nearly insurmountable hurdles to obtain special permits allowing them to bypass EU sanctions to import demining equipment. Further development of cash transfer programmes could grind to a halt if the British government decides to stop financing programmes in northern Syria, despite the incredible need there, out of fear of further media scandals related to the diversion of cash assistance. The same could happen if German and international development banks decide to cut off cash to humanitarian workers in favour of having them provide assistance in the form of water, food, and tents. Such actions could be a way of ensuring that each recipient of even one cent is not on the list of individuals sanctioned by the EU, in an attempt to equate risk management amongst the hail of bombs in Yemen to building a day care in Frankfurt am Main.

All of these issues threaten the core of the “Grand Bargain”. The network of European humanitarian organisations, VOICE, has already sounded the alarm, calling for the “Grand Bargain” to be saved. This cry for help is particularly aimed toward Germany, as many of the former largest humanitarian donors in the USA and Europe seem to be questioning the founding principles of a selfless and unconditional humanitarian action. But for this to be possible, there remains the need for a German foreign minister that is ready and willing to invest more political capital in humanitarian action. If the “Grand Bargain” has any chance of survival, it is in desperate need of some German emergency assistance.

This comment was published in the October issue of welt-sichten and can also be read on their website (only in German).

If you would also like to learn how the humanitarian system has changed over the last three years and what the German response to these challenges is, we recommend watching the recording of this year’s symposium “Humanitarian Aid in Transition“.