| Author: | Ralf Südhoff |

| Date: | 28. September 2024 |

What Germany’s new humanitarian strategy and a radically reduced budget mean for the future of its humanitarian aid

Scroll down to find an audio version of the blog!

After all, it has been completed. Germany, the world’s second-largest humanitarian aid donor, unveiled its long-awaited new humanitarian strategy on September 26th, 2024, after its old strategy had expired already in 2023. This delay sparked curiosity and indeed relates to an important reorientation of German humanitarian aid. But first things first.

Germany’s humanitarian policy holds immense importance during a pivotal time for humanitarian aid. On one hand, humanitarian aid is doing an amazing job supporting a record number of people in need and saving under highest risks millions of lives and livelihoods in crises and conflicts around the world. On the other hand, it is facing its own crisis: the value and principles of humanitarian aid are being fundamentally questioned, funding is more than ever short of needs, the international system is failing to substantially engage local aid workers and those affected, it has been failing for years to become more effective, more localised and better coordinated.

Few actors are trusted to bring about change as much as the German government, which has grown from a small payer to a leading, respected humanitarian donor over the past decade. Its new humanitarian strategy and future priorities are therefore of central importance, not only for its German and international partners but for the future of humanitarian aid as a whole. So, what does the almost 40-page paper contain? And perhaps more importantly, what might be missing—or has been removed at the last minute?

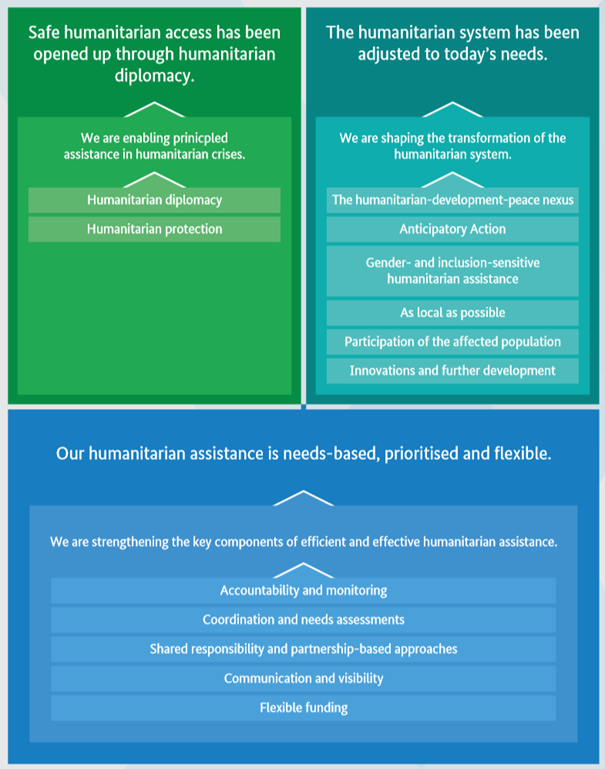

The new German humanitarian strategy sets out three guiding principles:

- Enabling principled assistance in humanitarian crises

- Shaping the transformation of the humanitarian system to boost efficiency and effectiveness

- Strengthening key components for efficient and effective humanitarian assistance

Each of these guiding principles is broken down into objectives that are to be pursued within its framework. Principled assistance is to be promoted through ‘Humanitarian Diplomacy’ and ‘Humanitarian Protection’. Transformation will be achieved through a focus on issues such as gender, innovation, localisation and close integration with development cooperation and peacebuilding (Nexus), among others. Efficiency and effectiveness are to be increased through coordination, ‘shared responsibility’, flexibility and ‘accountability’, with a strong emphasis on ‘efficiency’ throughout the strategy.

Theory of change – measures and activities; Source: Federal Foreign Office strategy for humanitarian aid abroad, September 2024

These goals are contextualised in their individual chapters, sometimes in detail and sometimes briefly, allowing the strategy to capture many of the central challenges facing humanitarian aid. This follows seamlessly from the previous strategy from 2019, which experts agreed offered a solid analysis of the current state of humanitarian assistance -but failed to go beyond that.

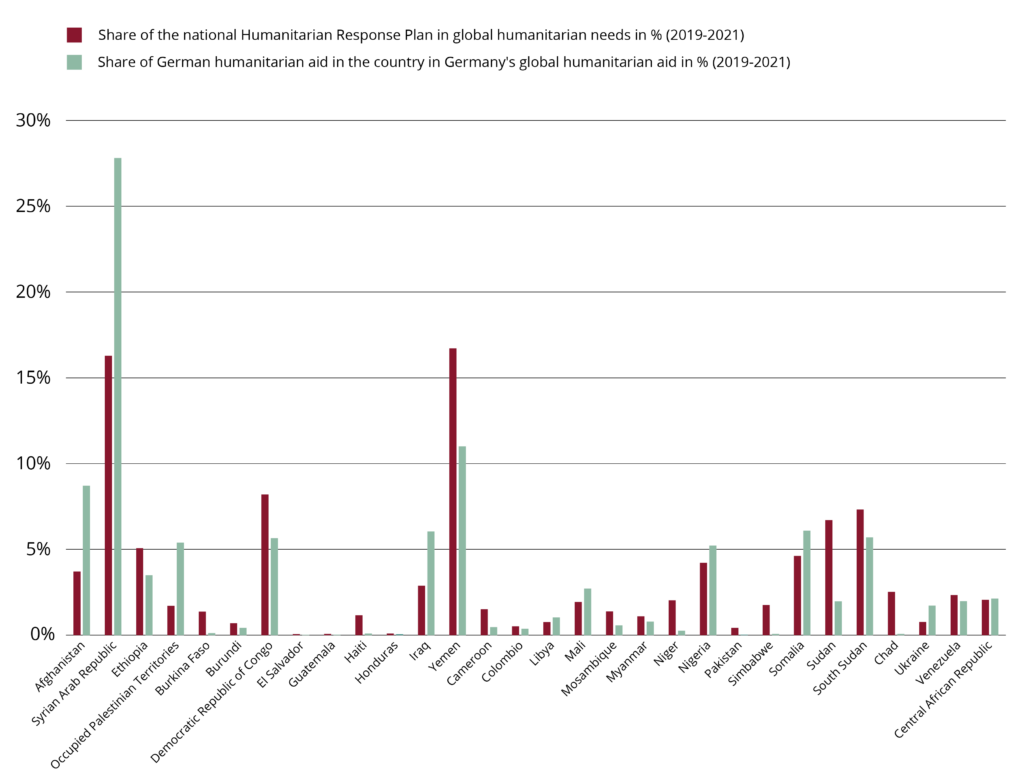

This was also reflected in the international perception of German humanitarian aid after 2019: Few donors were seen – at least until the start of the Gaza conflict – as so value driven, apolitical and committed to humanitarian principles as Germany. CHA analyses confirm that this perception has been reflected financially, with Germany consistently providing the most humanitarian aid where the need is greatest. (see chart). In recent years, Germany has come close to being a role model of a principled payer. Unfortunately, it is also seen as a model of an underperforming player.

Share of global humanitarian assistance and Germany’s humanitarian funding by country

Source: Report of the Federal Government on German humanitarian aid abroad 2018-2021; FTS OCHA 2023; Global Humanitarian Overview 2021

Over the last ten years, Germany’s strategic approach to advancing much-needed reforms in humanitarian aid has often remained unclear, not only to international partners. A notable exception was something that was not even a focus of GFFO’s last strategy: anticipatory humanitarian action. In recent years, Berlin has given considerable attention to this issue, placing it prominently on the international agenda, supporting it with human and financial resources (at least 5% of the humanitarian budget), and consistently pushing it forward. However, beyond this, international experts and Germany’s partners have repeatedly returned to the question: What are Germany’s goals and positions on the reform and existential issues that the humanitarian community has been ineffectively discussing since at least the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016?

This makes the question all the more exciting: What has the Federal Foreign Office learned from its old, largely ineffective strategy?

Initially, quite a bit: About a year ago, GFFO’s new humanitarian strategy seemed to be in its final stages, with publication planned for 2023. The foundation was to be a thorough evaluation of the previous strategy, along with the development of potential goals and measurable indicators for the future. GFFO staff at the time acknowledged that the old strategy had become entangled in countless topics and areas of work that Germany simply could not manage. Unlike traditional top donors (such as the USA, UK, and ECHO), GFFO does not have the staff in Berlin or at its embassies to handle all relevant humanitarian issues. The European Commission alone has around 450 highly regarded humanitarian experts located in crisis hotspots and hubs worldwide. By its own admission, Germany does not have a single staff member at its embassies dedicated to humanitarian aid; if there are any, it’s only a secondary responsibility. Moreover, the GFFO’s current political leadership of GFFO repeatedly emphasised that staffing gaps will remain.

This reality check on the strategy was acknowledged at the working level: in 2023, the humanitarian units aimed at four, a maximum of five topics as clear, genuine priorities for the coming years. The new model was not to follow the approach of other top donors by trying to cover all topics (and thus constantly being ‘behind the curve’, as one former manager described it), but to focus on depth in a few topics rather than breadth. This approach mirrors the strategy of high-profile medium-sized donors such as Switzerland, Sweden and Norway.

Some of the priority topics discussed a year ago have indeed made their way into the final strategy. However: alongside a dozen other “priorities,” all intended to serve the interests of the Foreign Office as a whole. Concrete goals, success indicators, or strategies for achieving these objectives are largely missing.

There are notable exceptions: the chapter on localisation is the most detailed in the entire strategy. It surely does not meet the expectations of most local actors, in particular, and addresses “participation of the affected population” only briefly and is focusing primarily on intermediary rather than local organisations. But it does present a thorough coverage – aligned with the latest international debate – of how the goals agreed upon in the Grand Bargain and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) are to be monitored more rigorously than before by donors, INGOs, and UN organisations. In areas such as gender, aid flexibility, and multilateral engagement, the Foreign Office has also made significant progress or sets clear ambitions in the strategy, along with strengthening humanitarian diplomacy and the humanitarian role of its embassies.

However, these examples also underscore the challenge posed by the numerous goals and supposed priorities. For instance, the goal of strengthening embassies – where will the personnel and funding come from if the humanitarian departments in Berlin are already severely understaffed? For instance the immense task of Humanitarian Diplomacy – how will the necessary staff or even a so far non-existent travel budget be secured for the newly appointed Special Envoy for Humanitarian Diplomacy, who currently juggles this responsibility alongside her duties as department head, almost in a volunteer capacity? This doesn’t even account for the political resources needed to navigate humanitarian diplomacy issues and its tensions with foreign policy objectives vis-à-vis politically sensitive partners like Israel, Saudi Arabia, or the United Arab Emirates.

The issue of setting priorities is not just about the perennial topic of funding but also about political capital. Take, for example, the identified priority of better integrating humanitarian aid, development cooperation, and peacebuilding—probably one of the most complex international challenges. In Germany, this has long been a point of contention, particularly regarding the rivalry between the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the Foreign Office. In 2018, the Ministry of Finance’s “Spending Review” reprimanded both ministries, urging them to at least establish working groups to share information about their respective plans in different countries. Six years later, the new strategy includes a commitment to “expand” these exchange processes to additional countries. Furthermore, there is still hope for realising a pilot project for a joint fund for initiatives in the Lake Chad region.

The overall conceptual direction of the strategy is undoubtedly relevant and likely enjoys broad consensus. The challenge, however, is that in strategic processes, consensus often stands for a lack of specificity and the avoidance of difficult yet necessary prioritisation—especially when doing so would raise internal and external power dynamics.

Nevertheless, the strategy outlines many valid goals that nearly all humanitarian actors can agree on. However, the same cannot be said for the new introduction to the strategy. It is no coincidence that this section underwent the most extensive rewriting during the approval process after the strategy had been almost finalised by the humanitarian departments. The significant shift in emphasis compared to the old strategy is most apparent in this section:

In the first paragraph of the previous guidelines, it stated that German humanitarian aid served “exclusively to achieve humanitarian objectives” and was “an expression of our ethical responsibility and solidarity with people in need.” The humanitarian departments at the Foreign Office defended the humanitarian principles and the allocation of funds based solely on greatest need so rigorously—or, as some critics put it, so “ideologically”—that they earned the nickname “Taliban in the Office.”

The introduction to the new strategy initially presented a purely humanitarian mandate, written so briefly and apolitically—just one page long—that even some civil society humanitarian actors were taken by surprise. However, in light of recent controversies surrounding the purpose and funding of German humanitarian aid, a significant tonal shift occurred during the final stages of the strategy’s development. The very first heading in the new strategy now reads: “Humanitarian assistance is part of the Integrated Security concept.”

Furthermore, the document is now filled with multiple references to security policy issues and the “National Security Strategy.” In the first paragraph, it states:

“Where people lack the essential resources they need to survive, where they lack food, hotbeds of social discontent form. Terrorist groups and armed militias attract members and the collapse of public order can destabilise entire regions in the affected countries. In our interconnected world, all humanitarian crises can potentially have a global impact. Often, German security interests are directly affected.”

Is this just pragmatic security semantics aimed at interest-driven rather than value-based coalition partners?

While the document, especially beyond the heavily edited first pages, frequently emphasises humanitarian values and principles, further changes feed the suspicion that this is more than cosmetic concessions. For instance, the original explicit renunciation of regional priorities for its aid to ensure a priority on greatest needs has been removed. A change already hinted at by the upcoming withdrawal of German humanitarian aid from Latin America.

Obviously a faction within the Foreign Office is increasingly gaining influence which has long advocated not for alleviating the greatest need per se, but supporting those in need where it aligns with foreign policy objectives. State Secretary Baumann openly confirmed this approach during the strategy’s release, stating: “(…) the numbers are going up, while the funds are decreasing. (…) So how to deal with this conflict? For us, this clearly means an even stronger focus on those crises that could impact the situation here in Europe and in Germany. So, conventionally speaking: We need to prioritise.”

In this context, the current national and international debate on prioritisation turns into a doubtful debate on politicisation.

The step towards the new German liberal party FDP narrative of cutting humanitarian aid and limiting it to allied states in the alliance against Russia seems imminent, especially with the planned radical reduction of funds.

This raises the critical question: What remains of a strategy whose resources were halved right before its finalization?

The cabinet-approved budget plan includes a 53% cut in German humanitarian aid, reducing the total to just over €1 billion. This would bring the humanitarian budget to a 10-year low, pushing the once-highly praised donor Berlin not only behind the top donors but also below current funding of countries like Norway, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. Besides, around half of the remaining €1 billion for 2025 is already allocated due to multi-year commitments. The remaining funds will likely be directed primarily toward politically relevant major crises such as Ukraine and Gaza, as well as support for Syrian refugees in the Middle East for migration-related reasons. This raises concerns about how much funding will be left for other crises in Asia and Africa—and what value a strategy has that merely normatively asserts: “For us, there are no forgotten crises.”

“If the budget stays as it is, the strategy is largely irrelevant,” is the assessment not just of radical critics but also of some humanitarian actors within the Foreign Office itself. Meanwhile, the leadership of GFFO has already stripped the new strategy of its ambition to be a “leading donor” in humanitarian aid, a goal that was still present in several paras in earlier drafts.

But why do the strategic aspiration and budgetary reality of GFFO all of a sudden diverge so drastically?

Humanitarian actors are rightly criticising the Chancellery and the Ministry of Finance for once again demanding disproportionately large cuts for the 2025 budget from the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), particularly from the GFFO, which faces another 17% reduction in its overall budget. However, this alone does not account for the historically unprecedented and disproportionate 53% reduction specifically to the GFFO’s budget for humanitarian aid.

Certainly, flexible project funds such as those for humanitarian aid, typically endure a greater burden during budget cuts compared to fixed costs like personnel. But a cut three times larger than the overall reduction? That’s unprecedented. It cannot be attributed solely to a tough finance minister, inflation, or indicated rising costs for cybersecurity. For example, in 2021, the Foreign Office had a total budget only slightly higher than what is currently planned—and yet the ministry was able to provide more than twice as much humanitarian aid (€2.14 billion) as is planned for 2025.

A similar trend emerges from the overall budgetary balance of the current coalition: in 2021, the current government inherited a humanitarian budget of €2.57 billion and promised in the coalition agreement to further increase it. Now the same government plans to cut humanitarian aid by almost two-thirds during its term. And it is questionable that a future government will allocate significant funds to rectify this historic mistake. This raises the overarching question: As how relevant does the Foreign Office rate its own strategy and humanitarian aid?

The new strategy was accompanied by high expectations, both internationally and nationally. The pressing question has been whether Germany will take the next step and bridge the gap between being a leading “payer” but an underperforming “player”.

Bridging this gap is still achievable, but it would require two things. First, the Foreign Office must decide on a clear cut thematic prioritization, by now over the course of the strategy’s implementation. Second, the federal government must decide on a clear cut financial prioritisation of the humanitarian budget in the remaining parliamentary process until mid November.

If these steps are not taken, the Green-led Foreign Ministry may go down in history as having closed the gap of being a major humanitarian “payer” but a minor “player” only in a rather peculiar manner: by turning Germany into neither a payer nor a player.

_________________________________________

Ralf Südhoff has been founding director of the Centre for Humanitarian Action (CHA).

Listen to the Blog (created with Murf AI):

Related posts

Principled Payer, but Purposeful Player?

19.10.2023Out of the box: Strategy Snacks 4

29.05.2024 12:30 - 13:45German Humanitarian Action