| Author: | Kristoffer Lidén and Kristina Roepstorff |

| Date: | 16. October 2020 |

Red Lines and Grey Zones: Ethical dilemmas in humanitarian negotiations and the need for a research agenda

When turning humanitarian principles into practice, humanitarian organisations are faced with a range of difficult ethical dilemmas. These dilemmas are rarely as tangible as when the organisations negotiate with local counterparts for access and programming in settings of armed conflict. This dimension of humanitarian negotiations remains to be systematically studied, and we hereby argue why this needs to be redressed as part of the ethics of humanitarian action.

Providing humanitarian aid is easier said than done. When humanitarian organisations distribute food, treat the ill, or evacuate civilians during wars and disasters, they engage in recurrent negotiations with the actors controlling the territory and population, such as state ministries, armies or opposition groups (Grace, 2020a; Clements, 2020; du Pasquier, 2016; Acuto, 2012). These negotiations put the humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence to the test (Grace, 2020b; Menkhaus, 2012; Magone et al., 2011). When their counterparts are violent militaries or partisan politicians, organisations may define red lines beyond which they can no longer justify their assistance. Forced to choose between uncomfortable compromises and inaction, this often leaves them operating in humanitarian grey zones on the fringes of ‘the humanitarian space’ (CCHN, 2019b: 279-309, 340-374; Hilhorst and Jansen, 2010).

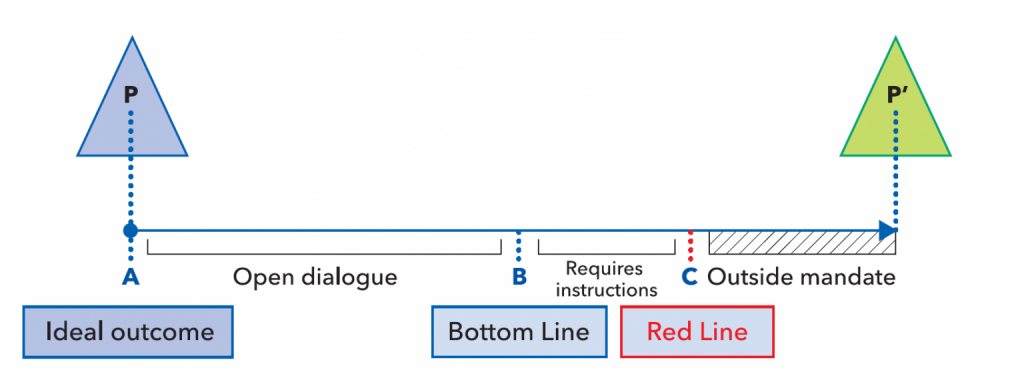

The ethical dilemma can be illustrated by an example. Imagine a situation in which a humanitarian organisation seeks to provide food aid to desperately hungry people in an area controlled by a militia. The organisation’s ethical principles dictate that no food rations be used to support a war effort. But the militia insists that it will prevent any food distribution unless food aid is also provided to its healthy soldiers. If the organisation maintains its ‘red line,’ innocent people will die from starvation, a result at odds with the organisation’s humanitarian mission. To prevent this result, the relief organization may venture into a grey zone, where principles are bent in an effort to negotiate a compromise. The compromise could be that food will be distributed to the starving as well as to soldiers’ families, under the pretence that they are also poor, if not starving (cf. CCHN, 2019b: 290). Those negotiating the compromise rarely have just one option but instead, must choose among several non-ideal ones. In this example, other solutions could be to allow the militia itself to distribute the food, or to involve a third party, like a UN peacekeeping force, in the negotiation. Figure 1 from the CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN, 2019b: 287) offers a diagram that depicts the negotiation space between the humanitarian organisation (P) and its counterpart (P’).

Thus, defining red lines and negotiating within grey zones involves making hard choices that have ethical repercussions. Concerned to adhere to the principle of humanity – that action must be taken to prevent and alleviate suffering wherever it may be found – humanitarian organisations set the bar for withdrawal exceptionally high and allow the grey zones to be accordingly wide in comparison to others engaging in benevolent international work. Quoting a humanitarian negotiator par excellence, Jan Egeland: ‘If you are there to help the victims from the depths of hell, you have to speak to the devil’ (Hoge, 2004). As such, humanitarian negotiations exemplify what has elsewhere been discussed as moral dilemmas, tragic choices, ‘dirty hands’ problems, emergency ethics and non-ideal theory (Slim, 2015: 163-167).

No one acknowledges these dilemmas more than the practitioners themselves. A survey conducted by the Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN) in 2017, identified recurrent dilemmas faced by humanitarian negotiators. These include balancing security rules with proximity to beneficiaries, denunciation/advocacy with silence, and impartial assistance with conditional assistance, as well as determining how much to compromise on sensitive issues of international humanitarian law and human rights, and whether to even engage with ‘controversial’ counterparts (CCHN, 2019a: 11). These dilemmas, which reflect the familiar ethical quandary of how to do good without directly or indirectly doing harm (Slim, 2015: 183-230; Lepora and Goodin, 2013; Ahmad and Smith, 2018; Anderson, 1999), are at their most intense during negotiations, which amplify controversial conundrums of power, culture and complicity. Engaging with these actors may not only be interpreted as a recognition of their legitimacy and play in the hands of local power holders, but also exhibit clashes in cultural norms while advancing international hierarchies of power and privilege.

Although several distinct literatures address the ethical dilemmas faced by humanitarian organisations, these ethical dilemmas are so far receiving too little attention in the context of negotiations. This is however much needed in order to provide guidance for humanitarian practitioners for navigating this difficult terrain and make hard choices. The disciplines of international relations (IR), political science, law, anthropology, sociology, gender studies, human geography, history and medicine have all contributed descriptive accounts of humanitarian engagement and its social and political ramifications. Collectively, they offer a patchwork of empirical and theoretical perspectives that touch on humanitarian negotiation. In particular, recent investigations of the rise of humanitarian action as a mode of global governance since the end of the Cold War and during the global War on Terror are essential for grasping the contemporary political character of humanitarian negotiations (Barnett, 2011; 2008; Donini, 2012; Acuto, 2012; Duffield, 2019; de Lauri, 2016; Hoffman and Weiss, 2018). None of these directly tackle the issue of ethics and humanitarian negotiation though.

The multi-faceted field of global ethics (which includes international ethics, global justice, and international political theory), on the other hand, has examined at length the specific issue of armed humanitarian intervention and the ‘responsibility to protect’ (Wheeler, 2000; Holzgrefe and Keohane, 2003; Bellamy, 2009). These studies explore issues of relevance to humanitarian negotiation, such as the tensions between global humanitarian norms, on the one hand, and the principles of state sovereignty and self-determination, on the other (Brown, 2002; Roepstorff, 2013; Lidén, 2014). But humanitarian intervention, and the military or political coercion it implies, is not what is at stake in most humanitarian access negotiations, which relies on pragmatic political support from local and international stakeholders (Barnett, 2013; Koddenbrock, 2016; Dijkzeul and Sandvik, 2019; Lidén, 2019; Roepstorff, 2020). Moreover, the need for better accounts of international engagement in ‘non-Western’ contexts remains within the study of global ethics (Sen, 2010; 2017; Erskine, 2012; Gaskarth, 2015; Lizée, 2011; Hutchings, 2018), and the ethics of humanitarian negotiations puts such accounts to the test.

More recently, several books and articles have begun to address the ethical problems that humanitarian actors are confronted with in their daily work, including those related to gender, class, ethnicity and religion (see also Zack, 2009; ICRC, 2015; Löfquist, 2017; Givoni, 2011; Rubenstein, 2015; Schneiker, 2017). These significant contributions do not specifically discuss the matter of negotiation, however, and they generally take humanitarian norms and principles as their frame of reference, reinforcing the ‘humanitarian reason’ (Fassin, 2011). As of yet, there are no analyses of the ethics of humanitarian negotiation. Such understandings of a neglected aspect of world politics are of immediate practical relevance, but they would also inform general scholarship on humanitarian action and the ethics of international engagement across cultural and political borders.

We thus propose a research agenda that seeks to close this gap in scholarship on humanitarian action and that provides a framework for ethical decision taking for humanitarian practitioners confronted with moral dilemmas. Such a research agenda should be based on theory and methods for empirical research on the subject (descriptive ethics) as well as philosophical analysis for the evaluation of the ethical problems (applied ethics) and include, among other things, studies that

- Investigate the ethics of humanitarian action from the epistemic perspectives of the individuals and institutions engaged in humanitarian negotiations, including local actors from the Global South.

- Map and systematically analyse ethical dilemmas faced by humanitarian negotiators.

- Identify different approaches to negotiations and responses to ethical dilemmas by humanitarian practitioners and organisations.

- Examine the process of establishing red lines by humanitarian organisations and the handling of grey zones by humanitarian negotiators.

- Uncover the cultural norms informing humanitarian negotiations and discuss their potential clashes.

- Micro-studies and in-depth case studies of humanitarian negotiations in different contexts and with different actor constellations.

References

- Acuto M (2012) Negotiating Relief: The Dialectics of Humanitarian Space. Hurst and Co.

- Ahmad A and Smith J (2018) Humanitarian Action and Ethics. 1st ed. London: ZED Books.

- Anderson MB (1999) Do no harm: how aid can support peace – or war. Boulder Co: Lynne Rienner.

- Barnett M (2011) Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Barnett M (2013) Humanitarian governance. Annual Review of Political Science 16: 379-398.

- Barnett MN and Weiss TG (2008) Humanitarianism in question : politics, power, ethics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bellamy AJ (2009) Responsibility to Protect: The Global Effort to End Mass Atrocities. London: Polity.

- Brown C (2002) Sovereignty, Rights and Justice: International Political Theory Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- CCHN (2019a) CCHN Facilitator Handbook. Center of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation.

- CCHN (2019b) CCHN field manual on frontline humanitarian negotiation. V2.0. Geneva: Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN).

- Clements AJ (2020) Humanitarian Negotiations with Armed Groups : The Frontlines of Diplomacy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- de Lauri A (2016) The Politics of Humanitarianism: Power, Ideology and Aid. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Dijkzeul D and Sandvik KB (2019) A world in turmoil: governing risk, establishing order in humanitarian crises. Disasters 43(2): 85-108.

- Donini A (2012) The Golden Fleece: Manipulation and Independence in Humanitarian Action. Kumarian Press.

- du Pasquier F (2016) Gender Diversity Dynamics in Humanitarian Negotiations: The International Committee of the Red Cross as a Case Study on the Frontlines of Armed Conflicts SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2869378.

- Duffield M (2019) Post-humanitarianism : governing precarity in the digital world. Medford, MA: Polity.

- Erskine T (2012) Whose progress, which morals? Constructivism, normative IR theory and the limits and possibilities of studying ethics in world politics. International Theory 4(3): 449-468.

- Fassin D (2011) Humanitarian Reason. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gaskarth J (2015) Rising Powers, Global Governance and Global Ethics. London: Routledge.

- Givoni M (2011) Beyond the Humanitarian/Political Divide: Witnessing and the Making of Humanitarian Ethics. Journal of Human Rights 10(1): 55-75.

- Grace R (2020a) The Humanitarian as Negotiator: Developing Capacity Across the Aid Sector. Negotiation Journal 36(1): 13-41.

- Grace R (2020b) Humanitarian Negotiation with Parties to Armed Conflict. Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies. 1-29.

- Hilhorst D and Jansen BJ (2010) Humanitarian Space as Arena: A Perspective on the Everyday Politics of Aid. Development and Change 41(6): 1117–1139.

- Hoffman PJ and Weiss TG (2018) Humanitarianism, war, and politics : Solferino to Syria and beyond. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hoge W (2004) The Saturday profile; Rescuing Victims Worldwide ‘From the Depths of Hell’. The New York Times, 10 April.

- Holzgrefe JL and Keohane RO (2003) Humanitarian intervention : ethical, legal and political dilemmas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutchings K (2018) Global Ethics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- ICRC (2015) The Fundamental Principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: Ethics and Tools for Humanitarian Action. International Committee of the Red Cross.

- Koddenbrock K (2016) The practice of humanitarian intervention : aid workers, agencies and institutions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lepora C and Goodin RE (2013) Complicity and Compromise. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lidén K (2014) Between Intervention and Sovereignty: Ethics of Liberal Peacebuilding and the Philosophy of Global Governance. University of Oslo Oslo.

- Lidén K (2019) The Protection of Civilians and ethics of humanitarian governance: beyond intervention and resilience. Disasters 43(S2): S210-S229.

- Lizée PP (2011) A Whole New World: Reinventing International Studies for the Post-Western World. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Löfquist L (2017) Virtues and humanitarian ethics. Disasters 41(1): 41-54.

- Magone C, Neuman M and Weissman F (2011) Humanitarian negotiations revealed : the MSF experience. London: Hurst.

- Menkhaus K (2012) Leap of faith: Negotiating humanitarian access in Somalia’s 2011 famine. In: Acuto M (ed) Negotiating Relief: The Dialectics of Humanitarian Space. Hurst and Co.

- Roepstorff K (2013) The politics of self-determination : beyond the decolonisation process. London: Routledge.

- Roepstorff K (2020) A call for critical reflection on the localisation agenda in humanitarian action. Third World Quarterly 41(2): 284-301.

- Rubenstein J (2015) Between samaritans and states : the political ethics of humanitarian INGOs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schneiker A (2017) NGOs as Norm Takers: Insider–Outsider Networks as Translators of Norms. International Studies Review 19(3): 381-406.

- Sen A (2010) The idea of justice. London: Penguin.

- Sen A (2017) Ethics and the Foundation of Global Justice. Ethics & International Affairs 31(3): 261-270.

- Slim H (2015) Humanitarian ethics: a guide to the morality of aid in war and disaster. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wheeler NJ (2000) Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zack N (2009) Ethics for Disaster. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield. This entry was posted in Blog and tagged ethics, humanitarian action, humanitarian negotiations, humanitarian principles on October 2, 2020 by Andrea Silkoset

This blog contribution was published on the blog of the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies on 2 October 2020. You can find the original post here.

Kristoffer Lidén is Senior Researcher and coordinator of the humanitarianism research group at PRIO.

Kristoffer Lidén is Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), Coordinator of the PRIO Research Group on Humanitarianism and Deputy Director of the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies (NCHS).

Kristina Roepstorff is lecturer at the University of Magdeburg (OVGU) and Associated Researcher at Center for Humanitarian Action (CHA) and the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) Ruhr University Bochum (RUB).